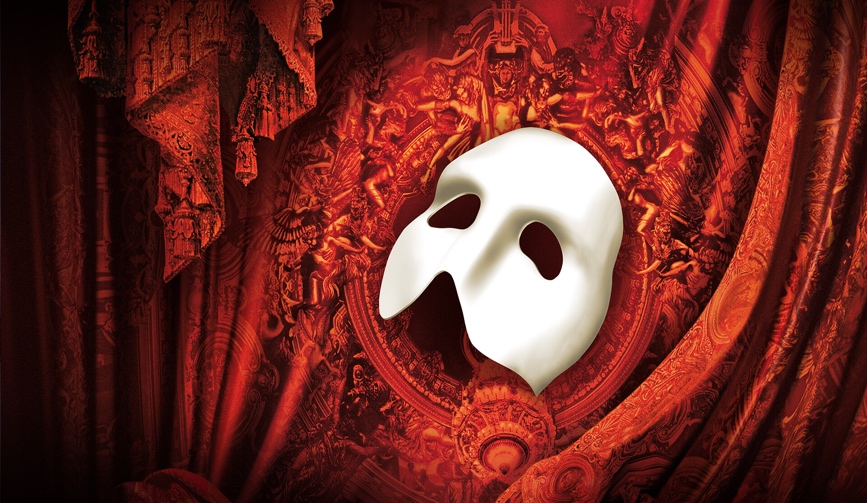

Embracing the Music of the Night: A Psychodynamic Perspective on The Phantom of the Opera as a Metaphor for Psychic Pain

Date added: 13/08/24

Embracing the Music of the Night: A Psychodynamic Perspective on The Phantom of the Opera as a Metaphor for Psychic Pain

By Claudia Kempinska (2024)

I saw the well-renowned musical production Phantom of the Opera this week. I drew some interesting parallels to clients’ experiences of trauma, PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) flashbacks, intrusions, and psychic pain.

Christine, the lead female role in the musical is helped, seduced, and tormented by The Phantom. The Phantom, from a psychodynamic perspective, could be perceived as a representation of collective past trauma. The audience experiences whisperings in the theatre; The Phantom’s ominous presence is indicated by the dramatic organ music and the looming chandelier above the audience which flickers and sways of its own accord.

Christine discusses her new singing tutor in the opening scene, which the audience later learns is The Phantom. Christine cannot name him, when talking to her peers, nor can his presence be made sense of by her. It appears that Christine is experiencing psychic pain.

Van Der Kolk and Newman (2007, p.7) argue that:

Post-traumatic syndrome is the result of a failure of time to heal all wounds. The memory of the trauma is not integrated and accepted as a part of one's personal past; instead, it comes to exist independently of previous schemata (i.e., it is dissociated).

Psychic pain is felt as intolerable and intense psychological suffering. At its extreme, prolonged psychic pain can lead to suicide attempts. Our nervous system is prepared from early in life to perceive the threat of physical pain. Defensive behavioural mechanisms which are mainly unconscious help us to avoid injury and preserve life. Examples of our nervous system at work include the impulses to fight, take flight, or freeze. Complex memories are stored for remembering painful experiences to avoid repeating them. Some of these memories are conscious and some unconscious. What can make recalling the memories especially difficult is when they are related to early childhood and/or when the pain has a strong emotional content. The emotional content which is not acknowledged can be extremely difficult to make sense of. Unpleasant and ‘undigested’ memories constitute the core of psychic pain.

Parallels can be drawn to clients’ traumatic experiences. A client may feel like the trauma must not be spoken about (particularly childhood sexual abuse, for instance). Clients may experience dreams, memories, or intrusions from the past that they cannot make sense of but have a level of awareness these intrusions are causing them distress. This distress may take the form of nightmares, anxiety, panic attacks, low mood, depression, and feelings of guilt. As well as clients in therapy we may also be able to identify with these types of experiences and dilemmas.

Christine’s father has died. In Act 2, she visits his grave and sings ‘Wishing you were somehow here again’ and sings the line,

Too many years. Fighting back the tears. Why can’t the past just die?

Once again, this reinforces the idea of traumatic past experiences being alive in the present and causing emotional distress.

No more memories, no more silent tears. No more gazing across the wasted years. Help me say goodbye.

Whilst Christine is singing about her father here, and longing for her father to be with her, she also notes the distress her grief and loss are causing her. Coupled with the distress caused by the seductive nature of The Phantom, she is desperate to make sense of what is happening to her. It is understood that her father made a promise to send her an angel to look over her. Perhaps in her unconscious wish to bring her father back to life, she is more vulnerable to The Phantom’s persuasion and control to believe he is linked to her father - the ‘Angel of Music’ that her father promised her.

Links can be made to clients’ psychic distress, and this can manifest in the psychological defence of splitting (Klein,1928). Clients may struggle to remember positive experiences when traumatic experiences are not integrated - parts of the self may be split off or disavowed and projected into others.

As previously mentioned, there are repeated reminders of death, despair, and the omnipresence of The Phantom. Another way this is demonstrated is by the character Buquet who dies by hanging. Buquet is a stagehand for the Opera Populaire - he is seen as someone who cannot keep quiet about The Phantom and is scolded by Madame Giry early in the story because of this. Madame Giry is thought to have rescued The Phantom as a child and wants to protect his ‘secret’, albeit at any cost.

This death could be seen to be a physical manifestation of the past impacting on the present, and a projection of all the psychic pain that Christine and The Phantom experience because of their losses – Christine’s being that of her father; The Phantom having to fear the world’s rejection due to his disfigured face.

Buquet is silenced by The Phantom, once and for all. This parallels some clients’ fears about speaking up about sexual abuse, or domestic abuse for fear of being harmed or killed by their perpetrator. Pain and fear can keep a metaphorical hold on clients and stop them from speaking out. Many clients describe feeling silenced, sometimes long after a perpetrator has died or is out of their life. Other clients describe being concerned with being in debt to or tied to the past. The noose that kills Buquet then, can represent a tie to the past and perhaps ‘killing off’ positive experiences.

The theatre owners are blackmailed by The Phantom. They fear that something bad will happen to someone - which it does. Clients often talk about fear of something bad happening again. Trauma is lurking in their body and mind, yet the traumatic experience has already happened. The past is being re-experienced in the present.

At the end of the musical, Christine ‘embraces’ The Phantom. As Christine kisses the Phantom, she silences the repeated ‘music’ of the night. The phantom releases her and her lover and she is freed from his spell; he disappears. This could be a metaphor for clients embracing and integrating the horrors they may have experienced in the past so that they no longer ‘haunt’ them.

Judith Herman reminds us that love and care are such important steps in the recovery from trauma. For Herman, without loving connections, the severely traumatized person is at risk of inner death (p. 194). Psychodynamic therapists help clients process trauma by creating a holding environment, making use of the therapeutic frame, and allowing the client to talk about past traumatic experiences. The therapist pays attention to unconscious processes, notices repeating patterns of the past, asks questions and makes interpretations to help the client gain insight. When this happens, it could be said that the phantom of the trauma can be laid to rest to create psychic peace.

References

Klein, M. (1928) Early Stages of the Oedipus Conflict, in, International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 9:167-180

Herman, J. (1997) Trauma and Recovery, Basic Books

Van der Kolk, B.A. and Newman, A.C. (2007) The Black Hole of Trauma, in, Van der Kolk, B. A., McFarlane, A. C. and Weisaeth, L. (eds.) Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body and Society, New York: Guilford Press

Get in touch

with me today

To find out more or tobook an appointment